Suicide

...it's complicated.

September was Suicide Prevention month.

I know it is a good thing. Raising awareness like this. Increasing access to support and reducing stigma…and yet every time I hear it, these words lodge themselves like bits of glass in my chest. They hurt. The word prevention can evoke all sorts of thoughts and feelings for those of us on this side of the equation. They tap into the blame, guilt and even shame that not surprisingly, lurks in the shadows in the wake of a death by suicide. When you find yourself standing at the edge of a huge hole blown into your life, it’s natural to ask, “What just happened, and could I have prevented it?”

For survivors, we crave a clear and simple explanation. The tendency is to over ascribe causality to what came just before the death. We wonder about that one thing that we did or did not do. I certainly have. This is painful territory, when the reality of suicide is so much more complex.

On World Suicide Prevention Day (September 15), I listened to Dr. Christine Yu Moutier (Chief Medical Officer for the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention) being interviewed by the grief expert, David Kessler. In this talk, she highlighted how the notion of prevention can be misleading and despite our best efforts, this does not mean that everyone can be saved. Like any other complex health outcome, not everything is preventable.

She highlighted that research demonstrates the cause of suicide is multifactorial. While recent life events can be relevant and contributing, the truth is a dynamic and complex interplay of anywhere between six to ten individual risk factors, involving both mental and physical health, occurring against a backdrop of ever-changing brain and body physiology, which at times can evoke states of cognitive constriction, despair and tunnel vision. At these moments, even the most robust of protective factors can get stripped away (like loved ones, connections to life, etc.).

Dr. Moutier noted that suicide is not a choice, and it is not a reflection of character or identity. It is a complex pathway for managing real and valid pain and suffering. She emphasized that people are generally doing the best they can with the support, resources and treatment options they can access. Despite this, there continues to be much stigma about mental health in general, and in that vein, death by suicide. This stigma is harmful for those who experience suicidal ideation and for those who are left behind after a death by suicide. I can’t even bear to address the horribly damaging notion that some religions offer up, that suicide is a sin. Seriously, fuck off. I don’t want that kind of a God anyways.

Dr. Moutier stressed postvention contributes to prevention. She calls on individuals and organizations to respond to deaths by suicide with caring, compassion and knowledge. Losing someone to suicide is associated with complex and traumatic grief, requiring more support for healing. Yet research shows there is less support offered by family and friends after a suicide death compared to other deaths. By raising awareness that suicide is a complex health issue, Moutier hopes for a societal shift towards more truth telling, where we can talk more openly about our pain and suffering instead of individuals “…spiralling down into a vacuum of silence.” In this way, we can be pro-active about our own health and wellbeing and that of our family members too. This is suicide prevention, much further upstream.

I recently participated in a beautifully held, online writing workshop with Rosemerry Wahtola Trommer titled The Mystery of Grief: Writing into the Loss. She suggested letting go of any pressure to write something “good” but rather, to simply tell the truth. Even if Jason is totally unencumbered now by everything that held him down during his earthly life, I want to set him free, and I remembered the truth does that.

Up until this point I have not be able or willing to speak much about suicide. Writing this post took me more than all of September. It has been difficult and not surprisingly, therapeutic. I have wondered repeatedly if I should share these more intimate details of Jason’s life. He held so much in secrecy and correspondingly in shame, but shame isolates us and is ultimately destructive. In order to break the silence and challenge stigma, I decided that Jason’s story is important and worth telling.

In the late spring of 2020, when COVID was ramping up, and before I knew him, Jason had attempted suicide. The COVID pandemic was challenging and devastating for many individuals. For Jason, having severe obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) centered around contamination fears, COVID wreaked havoc on his life. All recommendations for masking, hand sanitizing and avoiding people was exacerbating his illness. The social isolation was particularly challenging as he already lived alone, far from his loving and supportive extended family who are in another province. His world got smaller and smaller, which is essentially what OCD does to you. He was not working at the time. He had been in a car accident several months earlier and was getting treated for a spinal fracture that was causing unrelenting pain. He had been diagnosed with osteopenia/osteoporosis years earlier, which is unusual for someone his age and had been seeing a rheumatologist to improve his bone density. He had lots of fears about getting more fractures and how this would impact his body. He was not sleeping well. It was the perfect storm, and he saw no way out. His longstanding psychiatrist once told Jason she feared a suicide attempt was inevitable given the perfectionism inherent in his OCD and how it drove him to be so punishing and harmful to himself.

Jason survived when he absolutely should not have, it was a miracle of sorts and several months later, by a chance encounter, we met. Although Jason was eager to be my friend, he was reluctant to be in a relationship warning me that he was a “full time job” for himself. We just focused on getting to know each other. We wrote lengthy emails back and forth, shared pictures of beautiful things we saw during the day, and co-created playlists of music we each loved. At night after I put the kids to bed, I would quietly creep downstairs to my office, and we would spend hours talking on the phone. I had found a list of 200 questions to get to know someone more deeply, and Jason was open to the process, so every night we tackled a few more. We laughed a lot and did in fact, learn so much about each other. It was an oasis for us during a tumultuous time in the pandemic ridden world. Somewhere in there we fell in love. Our connection was so easy and natural, and in the space between us, we created something beautiful. There were many things about our individual circumstances that made things more challenging. Despite this, we championed each other. It was a profound experience for both of us, to give and receive love like this.

Right away, Jason told me about having OCD, something he had lived with since he was about four years old. It had added complexity and struggle to his life. Back when he was a kid, little was known about OCD, even getting a diagnosis took years. OCD had robbed him of many opportunities and life goals that you and I might take for granted. The OCD was entwined with depression. Jason spent much of his 51 years trying different meds, programs and therapy to manage his mental health. It interfered with full time employment and as a result he was on long term disability (LTD).

At the time, Jason was the first person in my inner world on LTD. I was suddenly confronted with my judgemental and socially constructed bias about what LTD said about an individual. Somewhere along the way I had acquired the idea that for anyone, most especially a man, to be seen as a valuable and acceptable member of society, they had to be engaged in paid work of some sort. It was a huge and humbling learning for me to face and overcome what had been until then, an unconscious and unfair bias. Through him and our connection, I got a big lesson in not objectifying people and seeing value in all individuals regardless of their circumstances. Ironically, after he died, I received a year of partial LTD benefits which allowed for reduced work hours so I could have the time and space for my continued healing.

Jason struggled with his own negative self judgements when it came to the reality of his life. A friend aptly noted how the LTD was like golden handcuffs. On the one hand, it provided him a steady income in the face of a true disability, however it absolutely interfered with his sense of identity and purpose in life. There was no flexibility with his insurance company in terms of his LTD. He was not allowed to experiment with part time work or different work environments. Earning any income or attempts at work could jeopardize his claim. It was an all or nothing thing. For such an intelligent man, this truly was a prison for him. Luckily, over the course of his life, his mental health challenges had, at times, taken more of a backseat, allowing him some amazing volunteer and travel opportunities, engaging in things he was passionate about, including anthropology and primates.

Jason held off telling me for quite some time about his suicide attempt. He was too scared, worried about how I might react, and how it might affect how I felt about him. It was a very powerful experience to process this together. Jason described the details of that morning. Convinced he would never get better physically or mentally, the rigidity of his OCD told him there was no other way. He said it was like entering a tunnel where nothing else mattered. Everything suddenly got quiet, where before there had been so much noise. Where there had been extreme anxiety, psychic and physical pain – after the decision, simply peace.

Jason also resisted sharing the truth in his recovery community. In his early twenties, he had discovered that alcohol was like a magical elixir in momentarily silencing his OCD and anxiety. But as it so often does when used as a coping strategy, alcohol wreaked havoc on his relationships and functioning. After some years of chaos, he ended up in AA and when I met him, he had a solid 20 years of sobriety behind him. Unfortunately, the shame about his attempt prevented him from becoming a sponsor, despite his tremendous wisdom and capacity to support others. But once again perfectionism prevented him from taking these steps. He believed he could not be a good mentor or role model given what he had done. The dark secret he carried, and the shame ate at him on the inside. In my eyes, it was a missed opportunity for meaning and purpose.

I was really struck by the fact that he could have died before we had an opportunity to meet. I wrote a poem which juxtaposed the things we were both doing at that exact moment in our individual lives. He said that reading my words was powerful, to see it laid out like that; It was another way to process what had happened. We joked that one day we would go on to write a book together, called Hemorrhoids and Suicide: charting the vulnerable territory of relationships, to raise awareness about OCD and suicide.

Whereas I was so grateful that he had survived, he struggled with the aftermath of the attempt. It did not bring him a sense of having a “second chance at life” that it can for some survivors. Don’t get me wrong, he was grateful to be alive, however certain aspects of his life became more difficult. He believed he now had mild cognitive deficits such as short-term memory issues, his OCD symptoms were harder to manage, and according to him, he became much more easily overwhelmed. Everyone who knew Jason well denied noticing anything different about him. However, his experience of himself was forever and negatively altered. He had much remorse, wishing so desperately that he had not done it and angry with himself that he had. Jason also lost the ability to cry, potentially because of his medications. This bothered him and I knew from my training with Dr. Gordon Neufeld, tears are essential for grieving and ultimately adaptation. Jason had much to grieve and adapt to over the course of his life, his mental health challenges, his physical health issues, the death of his father in 2018, his suicide attempt in 2020 and the death of his mother in 2022. Neufeld often says that the path of resilience is a path of tears. However, this emotional process that is wired into us, essential for moving through life challenges, was unavailable to him.

Over the course of our relationship, Jason was trying to find ground, self-acceptance and healing related to the attempt. He was simultaneously battling OCD, which was mostly a personal and private struggle for him. It was most intense when he was alone and not so obvious when he was in social connection. Being with others was medicine. My kids had no idea of his struggles. Jason had several brief, inpatient hospitalizations and two stints of community residential treatment to help him manage when his OCD symptoms got too overwhelming, or his meds weren’t working. He did private counselling and trauma therapy but there are next to no specific resources for those who have attempted suicide and survived. We talked about one day creating a group for attempt survivors, me as the counsellor and him as the person with lived experience. Jason also had difficulty accessing the very specialized support you need for OCD as Exposure Response Prevention (ERP) is mostly offered by psychologists costing upwards of $225/session. Although he lived a frugal life, preferring experiences over things, weekly therapy at this cost was beyond his means. He accessed general mental health support through Community Mental Health, which entailed a weekly phone call or in person check in with his case manager and monthly check ins with his psychiatrist. He did not find this to be very helpful. His medications were changed several times during our relationship which can be a challenging process to go through.

After many months, Jason was able to get a second opinion about treatment options from the psychiatrist who heads up the Mood Disorder Association of BC. He identified Jason as high-risk for a repeat suicide attempt and recommended either ECT (electroconvulsive therapy) or a trial of TMS (transcranial magnetic stimulation). This was hard for Jason to hear. ECT terrified him, so he declined this option and the TMS was put on the back burner because its use for OCD was experimental at best and accessing the treatment was logistically difficult.

We investigated psilocybin and other psychedelics which are quickly gaining more attention and popularity in their efficacy for the treatment of trauma and mental health issues. IV Ketamine treatment was very expensive and in the case of psilocybin, it was next to impossible to get authorized Health Canada approval for supervised therapeutic usage. Jason needed the involvement of his psychiatrist because of his medications. At that time, it was only approved for treating depression and anxiety in those who have a terminal illness. This seems very ironic to me now.

In early 2022, I discovered that Canada has one intensive residential OCD treatment program at Sunnybrook Hospital in Toronto which began in 2017. During one of Jason’s hospitalizations, an eager and super helpful psychiatry resident was willing to complete the lengthy referral. Jason was accepted into the program and six months later, in the fall of 2022, travelled to Ontario for the 10-week intensive program.

We were both holding our breath wondering if this would work as it was the highest level and most specialized support available in Canada. Within a few weeks, it was abundantly clear that it was, in fact, working. With another change in medication, and daily intensive ERP sessions, and group therapy, the OCD started to become more manageable, and the depression began to lift. His eyes grew bright with the possibility for a future again. For the first time ever, he was able to talk about the attempt with some compassion for himself, and recognize his illness was at the root. Jason started planning for moving to the island and wondered about the possibility of working again. He was doing so well that he was identified as a mentor for some of the other participants in the program. It was so great to witness this transformation. All the hard work and perseverance, despite the many roadblocks, seemed to be paying off. I remember that time with fondness. Seeing him and experiencing the fullness of him was such a treat. His sense of humour and his generosity of spirit expanded outwards.

In late November, there was a scheduled online discharge planning meeting which included Jason, me, his brothers and his care team. That morning, he had woken up with unusual leg pain and was sent to the ER at Sunnybrook. He was diagnosed with a blood clot in his thigh and put on blood thinners, and unfortunately missed half of the meeting while in the ER. Several days later he was leaving Sunnybrook and woke with hip pain but attributed it to a yoga class he had done the day before. It got worse during his flight home. After landing, on the advice of the nurse’s line he went right to the ER, to rule out another blood clot. After a lengthy wait into the early hours of the morning, he was diagnosed with a hip infection and given a dose of IV antibiotics. He was asked to come back later that day for an ultrasound and potentially more treatment. Upon his return to the hospital, so began that awful December snowstorm of 2022, the one where the entire transportation system was shut down in the lower mainland and people were stuck in airplanes for hours at YVR. Jason ended up stranded at the hospital for about twelve hours getting home in the wee hours of the morning. Shortly after, he started throwing up. He took a COVID test, and it was positive. The blood clot and the hip infection were symptoms of a COVID infection. It was stressful and disappointing re-entry for him.

Hours later, Jason was scheduled to start his online outpatient treatment with Sunnybrook. Given he was so sick and had not slept much in two days, he requested it be postponed. However, this was not possible because the Ontario clinicians only had temporary licensing for BC which could not be delayed. He ended up having to cancel many of his sessions because he was so sick and this outpatient phase of his treatment was significantly impacted. To partially compensate, it was arranged that a local Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) clinic would provide additional outpatient OCD support. However, given it was December there was no availability until the new year.

I now see this as a huge gap in care. Jason had completed a more than one hundred-thousand-dollar inpatient program and the crucial outpatient support that would help him translate his learnings and gains to his most triggering environment was next to none existent.

It was during this time Jason found out that his volunteer training at the Museum of Anthropology, would be cancelled due to the museum closing for seismic upgrades. This was an opportunity he had been very excited to come home to. It was one more thing that went wrong.

January 2023 was continued waiting for the outpatient CBT clinic. Jason had a follow up appointment with a hematologist in late January. The blood clots, despite treatment, had increased in size. The blood thinner dosage was increased. The OCD started to gain momentum again without adequate support. The hope created in the fall started to unravel. It was so disheartening for him to experience and awful for me to watch.

One week before he died, Jason phoned me and said that he was going to the hospital. I thought at first it was related to the blood clots. It was then he admitted he needed to go because his anxiety and OCD were so high it felt unbearable. He did not say he was suicidal. His psychiatrist happened to be on call that night. After being assessed, he was discharged home and told that he did not belong in the hospital, that he should go home and fight. We both understood what he meant and kind of agreed with him. It’s true, the hospital was not the right place. The psych ward was rather demoralizing and dehumanizing and it was just a stop gap. He needed ongoing specialized help that was not available at the hospital.

One of the reasons Jason had come to life at Sunnybrook was because he was in community there. He was surrounded by many others from across Canada, also receiving specialized support for various issues from eating disorders to PTSD to addictions. The group therapy aspect of the program was so healing for him. He saw he was not the only one who was struggling, and he no longer felt so alone. He took a risk and shared the dark secret of his suicide attempt, without being judged for it and even heard from others who had similarly attempted suicide.

Over the next week he continued to struggle but tried to shield me from it as much as possible.

On February 14th, he told me that he needed to go back to the hospital. This time he admitted that he was having thoughts of suicide. He promised me that he would not do anything to hurt himself. Yet he texted me saying, “Move on love of my life. You deserve so much more than this.” I also remember him saying that he wished that I was there. I realize now, in hindsight, if he had been going through cancer treatment and having a medical crisis, I would not have thought twice about asking for the next day off work and heading to the mainland that night. Despite my job as a counsellor, I realize now that I too, was subject to the stigma surrounding mental health issues. I had only told my closest friends about his OCD and depression and his treatment at Sunnybrook.

I assumed the hospital would admit him this time, given his history, and the hospital visit the previous week. Knowing that his phone would be taken away, I turned off my phone (which we both did every night) at 9:53pm. It turns out Jason texted me a mere 17 minutes later at 10:13 pm to tell me that he was being discharged. Having worked in a hospital, I know how it goes when a patient comes in repeatedly. “Frequent flyer” they are called. I am sure he was seen as such and there are a whole bunch of negative judgements that go along with that nickname. I imagine the psychiatrist on call saw the notes from the previous week, when his own psychiatrist had sent him home.

It was early the next morning when I checked my phone and saw his texts from the night before letting me know he was being discharged. One of the things he wrote was “Please tell me you haven’t gone to sleep.” This text was worrisome to me, and not the normal tone of his communication.

I got up and ready for work with a huge sense of dread. I tried calling, but his phone was off, which again was not unusual. Shortly after arriving at work, Jason reached out to me, and I audibly exhaled. We texted briefly and I said I had been worried about him. He texted back, “I am ok…I am going to go out and get groceries and get my car serviced.” As I was in the middle of working on something with a colleague, I said I would call him back within the hour. He immediately called me. I recall him saying something about being “safe and sound” and repeated to me his plan for the morning. I remember thinking …oh thank goodness, not only is he okay, but he is moving in a direction. We did not have time to talk about the details of the night before at the hospital. I assumed that would happen later.

I got caught up at work that morning, went from that meeting to several students in a row needing support. I texted Jason to say I would reach out at lunch. There was no response, however this was not out of the ordinary. I figured he was out and about.

I phoned Jason on my lunch break, but there was no answer. I texted several times during my very busy afternoon with students.

By dinner time with no response, all of sudden, I started to worry. There was a flurry of phone calls to his family, a friend who had keys to his apartment and a call to the RCMP for a wellness check. I immediately called my friend Amanda to come over and be with me while I waited for news. I think deep down I already knew, and I also knew he would not get it wrong this time.

Then came the phone call that confirmed he was dead. It was the worst moment I have ever experienced in my life. The seconds and hours and days after continued in that vein. I cannot find adequate words to describe the level of pain and devastation.

About three weeks after his death, his psychiatrist phoned his cell phone to check in. When his brother answered, his psychiatrist asked to speak to Jason. I could not believe it. His psychiatrist had no idea that Jason had died. How was this even possible? It just made me sick to my stomach. It reinforced the truth about the lack of mental health care in Canada and the huge gaps in the system.

I have said many times, it seems like the road was paved to his death. All the risk factors, male, 51, previous attempt, significant mental health issue, physical health issues and all the things that went wrong for him in the last couple of months of his life. I even wonder about the COVID infection as there is now research linking this virus to the onset or exacerbation of depression and impacts to serotonin levels. Despite my clinical training, I could see the risk, and yet I couldn’t. I somehow did not believe it was possible. Given his remorse and regret, I assumed this would never happen again.

In the early days of grappling with how to reconcile Jason’s death, and whether I was meant to intervene in some way and failed him, a wise elder said…

“I would affirm the possibility that Jason was telling a truth when he said he was okay. Of course, you and I can never know his state at that moment for certain. But your trust in yourself should not rest on any single moment, even one so closely preceding a tragic “fall”—but rather on the whole story of love that you shared through time.”

I now know without a doubt, Jason does not hold me or anyone else responsible for his death. I know he felt loved and supported by many and he felt trapped in a cycle of illness that he could not find his way out of, despite his best efforts. I constantly remind myself how much pain and suffering Jason experienced. He endured so much.

This has been such a difficult journey, trying to find my own peace and healing and adapting to life without his embodied presence. My thoughts about suicide have been all over the place. I wish he did not die this way, or die alone and yet he is also free now.

Next week, I start a 25-hour training based on the work of Gabor Mate called Suicide Attention training, to be distinguished from Suicide Prevention training. The description of this program notes, “Understanding suicidal feelings as a coping mechanism for those who are in significant emotional pain is far more helpful than a reactionary treatment focused on keeping the individual alive, which according to research has limited and short-lived efficiency … this program works at destigmatizing the subject by building a community environment where people feel safe to explore, express and understand this aspect of their experience.” I wish this type of approach had been available to Jason, even though it likely would not have been enough. As much as doing this training will require bravery on my part and lots of self-compassion, I want to be able to show up in a better way for the teens that I work with who grapple with suicidal thoughts.

Jason was a whole person who suffered from a debilitating illness. It took away his ability to work and build a career, foster a full social network, and even prevented him from owning a dog. It robbed him of the opportunity to reach his full potential or tap into a solid sense of meaning and purpose. Jason wanted so much more for himself and to be able to give more to others as well.

As I said earlier, one of my big worries about telling this part of Jason’s story is that he will only remembered for how he died. I don’t want these details to obscure the many other truths that simultaneously exist about him. That he was so much more than his illnesses or life challenges. That he was able to be playful and have fun, laugh, enjoy nature, exercise and care for his body, travel to far off places alone and with me, volunteer, spend fun times with me, my kids and his incredible family, love animals, enjoy poetry, and seek out experiences wherever he could. He was smart and so funny and had such a way with words.

He often expressed gratitude for the people in his life who loved and supported him, like his friends, family and me. Yes, at times, his illness was stressful for me, but all chronic illnesses are stressful. To be honest, I was mostly shielded from what it was really like for him. Many times, he apologized to me for not being able to show up as completely as he wanted to or felt that I deserved. However, my overarching experience of him was that of being loved and cared for. I was reading through some emails today and found something that he wrote during his program at Sunnybrook. This gives you a little flavour of him and how he supported me…

“Ali is the most caring and giving person I know. She is such a hard worker at her vocation- any student who’d have been in contact with her would be forever changed for the better. As a mother, she is so hands on it’s astounding (to her 2 beautiful kids.) She is beyond bright, is full of passion in everything she does. She is funny and silly and adventurous and cool and graceful and excitable and fun and lights up any room with her smile. Her almond shaped eyes will mesmerize you. She’ll love you with all that she has. She always brings a positive slant to the situation. She is by far my favourite primate.”

Jason was a beautiful, kindhearted and unique person with a horrible disease that wreaked havoc on his life. Despite this – he loved deeply and was profoundly caring and kind. I am blessed that our paths crossed, and that my kids and I got to love and be loved by him. We are forever changed by his death, but also by his life. Jason was so much more than the way he died. He was brave. Lover of adventure and experiences. Noticer of beauty and tiny details. I miss him every day. And I am glad his suffering is over.

Suicide is complicated.

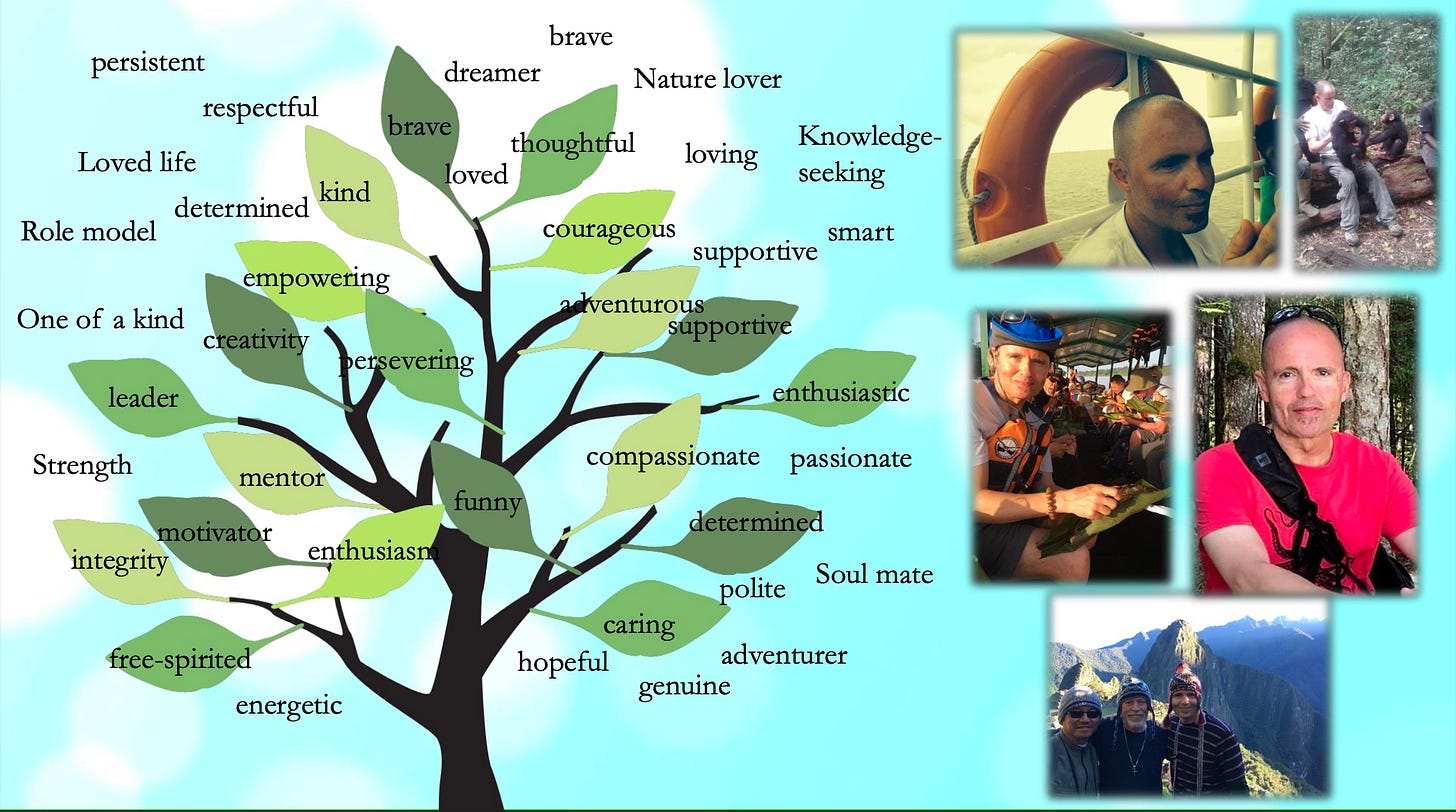

This image was created during an online memorial Sunnybrook hosted to celebrate Jason several weeks after he died. I was invited to join alongside the clinicians and program participants. Sunnybrook also hosted a fundraising OCD walk in his honour.

Here my song for this post, it was a meaningful one for Jason…

Wow. What a post Ali. Deep, profound, sad, informative. Thank you.

The resources are scattered and sparse, and not trivial to coordinate that’s for sure. In 2010 A friend and I made the Ride Don’t Hide charity To help get rid of the stigma behind mental illness and mental health issues. It has become worse and worse and worse after Covid. The fentanyl issues. Even with the hate between the far right and far left, etc. The stigma needs to go away. I’m proud of Jason. I’m proud of you.